As a non-Economist, this is how I believe the Bank of Ghana (BoG) and the Ministry of Finance (MoF) can use Quantitative Easing (QE) to support the economy without having to worry about inflation or any other shocks to macroeconomic indicators.

My working definition of QE in Ghana’s context is simply long-term Cedi borrowing (bond) by government from BoG at near-zero interest rate, that will give government cash to directly invest in quick-return domestic production for domestic consumption, while increasing the balance sheet of BoG.

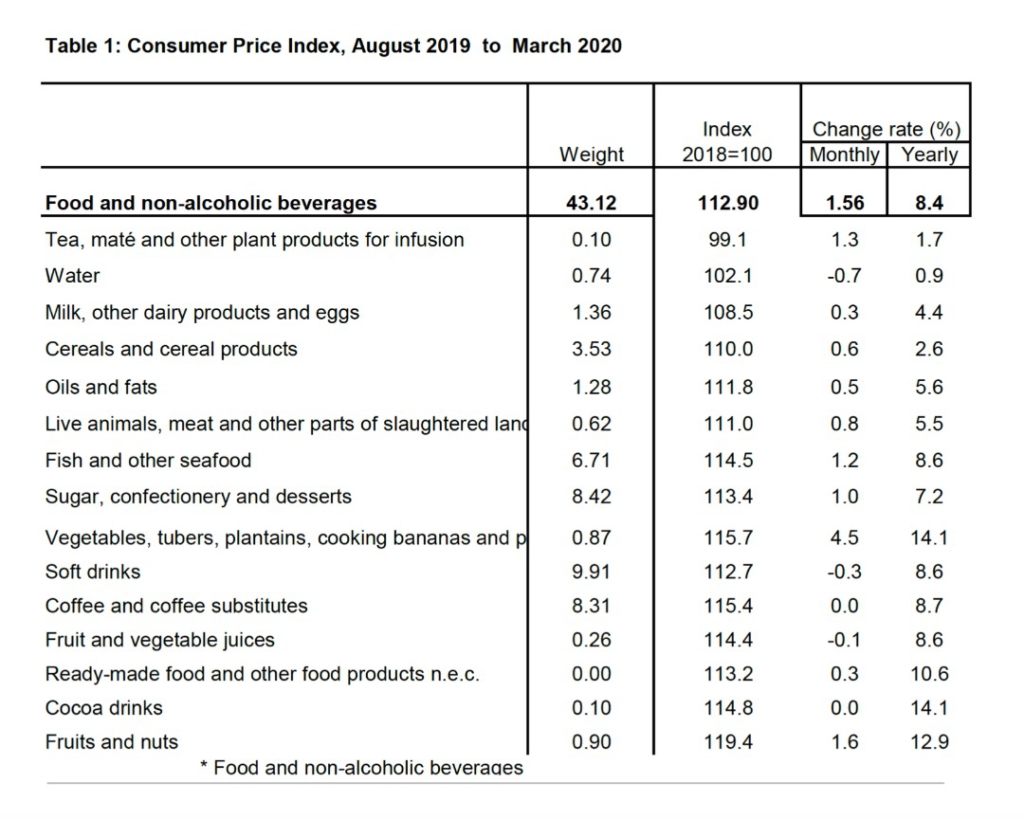

Please take a look at the ‘Food and non-alcoholic beverages’ CPI for March 2020 below.

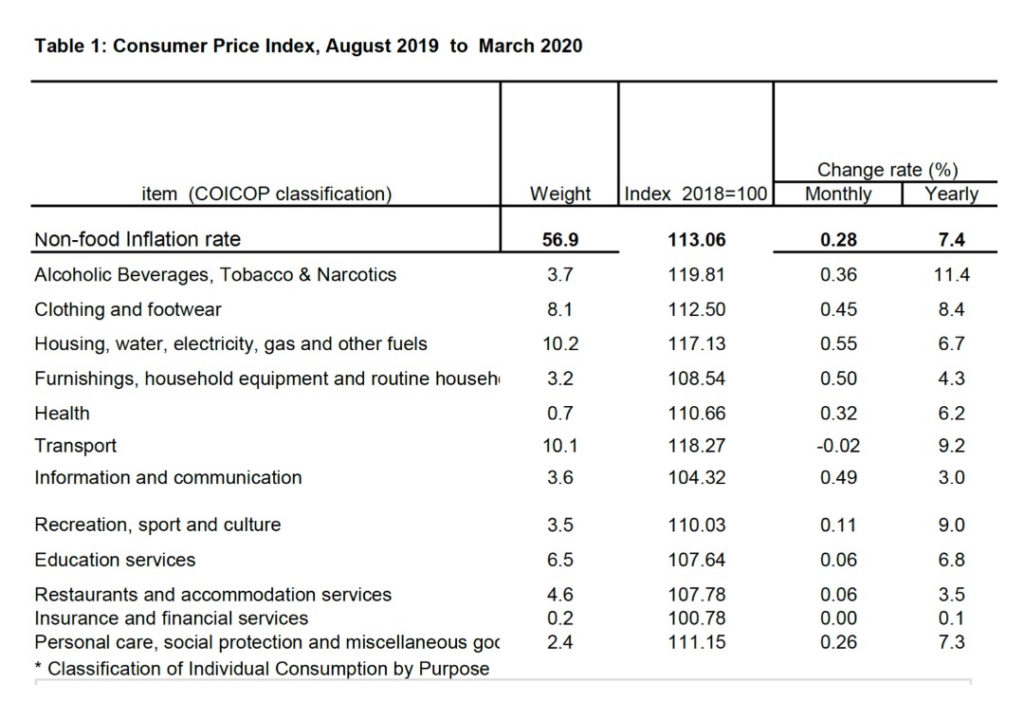

The ‘Food and non-alcoholic beverages’ category has yearly inflation rate of 8.4% compared to 7.4% for ‘Non-food’ inflation (see table below).

If we use QE to raise enough finance to produce every item in the ‘Food and non-alcoholic beverages’ basket, inflation will actually go down. Government, through the buffer stock company, can buy and store all excess produce. Government can also use part of the QE money for BOST to expand national strategic reserves, especially at this time that oil prices are going down. That will affect the Transport element in the Non-food inflation basket. Transport is only second to Alcoholic beverages in terms of its impact on the non-food inflation rate.

If we use QE to achieve self-sufficiency within the Food and non-alcoholic beverage category, for instance, we would be saving over US$400 million per year on imported chicken alone. Even on interest rates, if government provides QE money to all these agricultural and agro-based industries, it means those businesses won’t be borrowing from the banks. What that means is that the banks would be looking for new loan customers. Banks would be chasing individuals and other businesses with loans. There would be higher supply than demand for credit, which could drive interest rates down.

The reason QE has not been very successful in some developed countries is largely because their economies have in many cases reached peak production capacity such that there are not many avenues for expansion, especially for domestic consumption. And if that happens during a global financial crisis, for instance, it means production for export also becomes limited. So, under those circumstances, no matter how much more cash reserves a Central Bank would pump into the banking system, businesses are not keen to borrow, even at near-zero interest rates.

The case is vastly different in Ghana’s, because we have so much production and consumption capacity to absorb in all sectors, but especially so in manufacturing and agro-processing. The other difference between QE in developed countries and Ghana is the fact that the traditional relationship between inflation and interest rate isn’t exactly so in Ghana. We have over the decades had both inflation and interest rate very high, compared to developed countries. I’m yet to witness in Ghana the inverse relationship between inflation and interest rate. So those theories that say that QE will lead to lower interest rate and higher inflation won’t necessarily apply in Ghana. As I’ve explained above, using the QE money to expand food production will ensure that prices of those items in our inflation basket will rather go down. Let’s fashion our own economic model that is both practicable and feasible. As I mentioned from the outset, QE is simply long-term Cedi borrowing (bond) by government from BoG at near-zero interest rate, that will give government cash to directly invest in quick-return domestic production for domestic consumption. The multiplier effect on employment and other sectors of the economy can be anyone’s guess.

***

Kwaku Antwi Boasiako is Chief Operating Officer at Vintage Ventures Limited in Accra. He has senior management experience in diverse industries. He has an MBA from the University of Leicester, after his BSc. Admin from the University of Ghana